A reflection on Mark Twain, the long reach of story, and where Little Red Bear first found his voice.

On February 18, 1885, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was published.

More than a century later, the river is still moving.

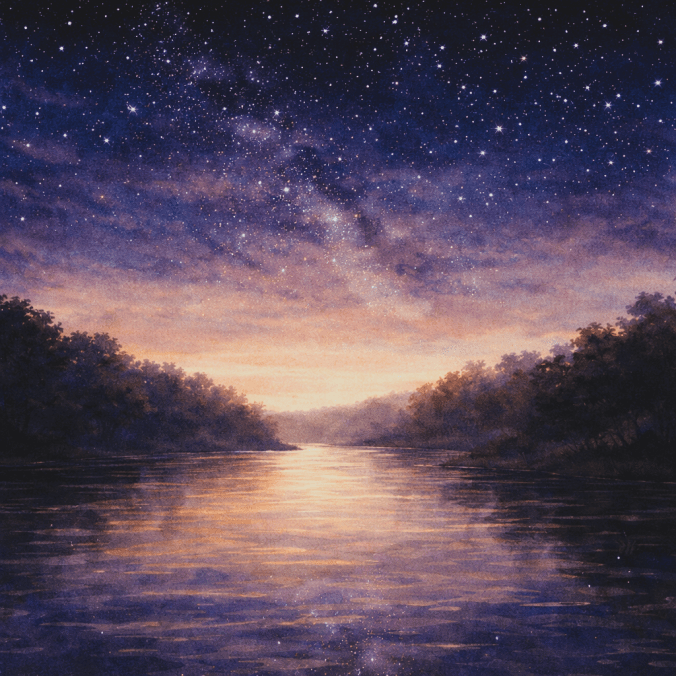

I first read Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn years ago — long before I understood what they were doing to me as a writer. Later came Life on the Mississippi, and more besides. At the time, I simply loved the stories. The raft. The sparks in the dark. The sound of the river settling back into itself.

Years later, walking through EPCOT at Walt Disney World, I wandered into a special exhibit of personal items belonging to Mark Twain. Behind glass sat a simple fountain pen he had once held in his own hand.

Not a monument.

Not a statue.

A pen.

I remember standing there, thinking about the ordinary act of writing — the scratch of nib against paper, the slow forming of sentences, the patience of revision. That pen had once rested between his fingers while he shaped rivers, boys, steamboats, sparks.

And I felt, in a very quiet way, connected.

There is a passage from Huckleberry Finn that has stayed with me all these years . . . .

![]()

“Once or twice of a night we would see a steamboat slipping along in the dark, and now and then she would belch a whole world of sparks up out of her chimbleys, and they would rain down in the river and look awful pretty; then she would turn a corner and her lights would wink out and her powwow shut off and leave the river still again; and by and by her waves would get to us, a long time after she was gone, and joggle the raft a bit, and after that you wouldn’t hear nothing for you couldn’t tell how long, except maybe frogs or something.”

![]()

It is not dramatic. It is not moralizing. It is simply noticing.

The sparks.

The bend in the river.

The long delay before the waves arrive.

There is something in that river passage that has followed me all these years — the way the sparks fall, the way the steamboat disappears around the bend, the way the waves arrive long after she is gone. Those gentle waves are still reaching me. Without my fully realizing it at the time, they found their way into Little Red Bear. He would not make a speech about it. He would simply watch the sparks, listen to the frogs, and notice how the raft rocks a little after the noise has faded. Red has always trusted the quiet aftermath more than the loud arrival. In many ways, I suspect that is where he was born — somewhere between Twain’s river and the stillness that follows.

Stories turn the bend.

The sparks fade.

The whistle grows faint.

The river grows still.

And years later, the waves arrive.

Some of them began their journey in February of 1885, though it would take many years before they reached a desk of my own. Some reached me standing in EPCOT, looking at a fountain pen once held in Mark Twain’s hand. And some are still arriving, rocking the raft just enough to remind me why I began writing in the first place.

If Little Red Bear ever feels steady beneath you, if his voice ever sounds like it trusts the quiet more than the noise, you now know where that began.

Somewhere on a river.

Somewhere after the steamboat turned the bend.

‘Till next time, then — Jim (and Red!)

![]()

![]()

P.S. from Little Red Bear

Sometimes the river seems still, but the current is moving steady and sure beneath the surface. Stories are like that. They keep shaping us quietly — and then one day, we notice the raft has carried us farther than we realized.

“The Adventures of Little Red Bear: The First Holler!”

![]()

These illustrations were created with the assistance of AI.